Mombasa's Geography:

At this point I have described two journeys which headed towards Mombasa, the first in 1950 when I was five, and the second in 1963 when I was eighteen. It seems appropriate therefore to describe something of the background to a place with which I associate the happiest days of my young life.

By the time we arrived in 1950 the island was joined to the mainland by the Makupa Causeway, which carried both the main road and the railway to Nairobi. To travel north along the coast one had to cross....

....Nyali Bridge, a pontoon bridge, which also gave access to Nyali Estate which was being developed for European housing.

The Likoni Ferry crossed to the south of the island, connecting to the road that ran south to Tanganyika.

This map is orientated differently but shows some of the main places in our young lives. 1 is the location of our first Mombasa house, 2 the second. Our third house was at Nyali, off this map. Our last house was at 3. The school which European children attended from age five to nine, the Mombasa European Primary School was - and still is - at 4. 5 is the beach we visited most frequently, the Swimming Club, which could be accessed by boat across the Old Port or via Nyali Bridge. When we first arrived the only place for a swim on the island was at the Mombasa Club, 6, where a pool was located on a coral platform below the club. Because it was down a flight of steps it was always referred to as the 'Chini Club' 'chini' meaning 'below' in Swahili. Finally, 7 was the location of the African Mercantile Company, the business for which my father worked.

In the early 1950s the population of Mombasa stood at about 120,000, of whom 61,000 were Africans, 36,000 of Asian descent mostly from the Indian subcontinent, 19,000 people of Arab descent, and 2,800 Europeans - but these bald figured give no idea of the wonderful mix of races and peoples which we encountered.

My thanks to Tony Chetham for the photos.

Arrival in Mombasa 1950:

When we arrived in Mombasa in 1950 we moved in to a bungalow in Cliff Avenue. In her 'Life', my mother described it as, "very ancient and riddled with white ants." The Champions, with their daughters Lynn and Felicity, had a similar bungalow next door.

In this photo which, again, dates from our early days in Mombasa, Richard and I are with Susan Gadd. I don't recognise the location so this may have been in the grounds of the bungalow.

The cat was Susan's but the dog, Susie, was Richard's. We had acquired Susie shortly before we left Dar-es-Salaam, a rough-haired dachshund who had a lovely nature. While Tinker flew from Dar to join us, Susie travelled by ship.

We were quickly enjoying Mombasa's beaches. This picture is from around that time and shows Richard and I with Zandra (right) and Rhonelda Shinn and their mother at the Swimming Club.

An old inner car tyre tube was an essential when we went swimming, as we would sit in it and paddle around. This picture is also at the Swimming Club, which was reached either by car, crossing Nyali Bridge, or by boat. In the latter case, one went to the Old Town, seen here across the harbour, and hired a 'water taxi', a rowboat powered by one man, which crossed to the Swimming Club pier. To summon the 'taxi' for our return journey, a flag was raised at the end of the Swimming Club pier.

Christmas 1950 was spent in the bungalow. Captain and Mrs Solly with their sons Mark and John came to lunch but before the meal could be served the 'house boy', Ouma, came through to say that the cook was drunk and was threatening the staff with a carving knife. My father and Captain Solly managed to get rid of the cook and Ouma served the meal. Ouma remained with us until we left Mombasa in 1961.

Mombasa's Beaches:

The beaches of the East African coast are superb. The sand is coral white, blinding in the midday sun. Behind the beach stand ranks of coconut palms whose fronds whisper in the breeze. Below the beach the sea floor shelves gently into deeper water until, about a mile or so out, it starts to rise again. Coral masses become increasingly frequent, merging until they build into the great hog's back of the fringing reef, on the outside of which the massive swells of the Indian Ocean smash themselves into a maelstrom of foam. The reef protects the lagoon, both from the worst of the waves and from ocean predators like sharks.

This is one of my favourite photographs. It shows Tony Chetham sitting astride a palm which leans out across the beach at Nyali. It puts our childhoods into context.

There are so many beautiful beaches along the coast to the north and south of Mombasa - Shelly Beach, Diani, Two Fishes, Nyali, Tiwi, Vipingo, Bamburi, Shanzu. This is Kikambala, with Avril Baxter, the girl who, according to my mother, gave me the name Jonathan, and I pulling Richard along the beach.

Low tide exposes miles of sand flats and coral pools, the latter filled with myriad sea creatures. With our skins tanned the colour of mahogany we could play out there for hours, even in the midday sun, until the tide started to slide in, the first advancing water hot from the heat of the exposed sand, rapidly deepening, drowning our castles and canals.

As the water deepened we put on goggles and swam out across the forests of sea grass duck-diving for shells, while at spring tides, when the water deepened enough for the ocean swell to come in across the reef, we sat in inflated inner tubes and paddled over the breaking waves. In this picture can be seen, far out along the horizon, the white of the breakers on the reef.

I have been back to that coast, not to Kenya because the beaches we remember are crowded with tourists and touts, but to Tanzania, where some of the beaches are as empty and as beautiful as those that crowd my memory.

Many thanks to Tony Chetham for the top picture.

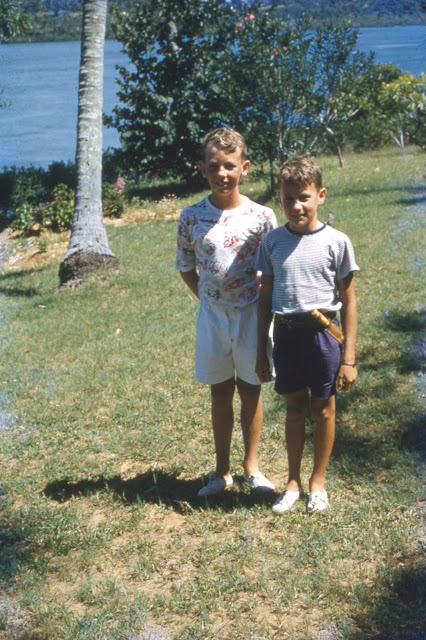

The Ansteys were also good friends of my parents. They had a house at Tudor, where this picture was taken. Mr Anstey was manager of the East African Breweries. Richard and I are in the Anstey's garden in typical daily wear: tee shirts, shorts, 'tackies' - plimsolls - and we always wore a small sheath knife - Richard's is visible in the picture.

The Swimming Club:

In her 'Life' my mother wrote, "After Sunday School the boys and I would return to the house and get our tricycles and my bike and swimming suits and go down to the Chini Club for a swim before returning to the house for lunch. Or we would go right down to the landing stage and get a rowing boat to take us across to the Swimming Club where we would eat our lunch which we took with us, and spend the afternoon swimming and playing in the sand, usually with the Solly boys and Margaret who sometimes took us over in her car. Dad would come later, having been at the Sports Club watching cricket, and take us home in the car."

The beach wasn't as good as those along the coast but we spent many happy hours on it. This picture shows us with the John (left) and Mark Solly. The yacht is mine. Called Defender after my grandfather's ship, it was made for me by one of the Harrison Line engineers.

Sometimes there were events at the Club. This group photo was taken on the steps of the club house.

The top three pictures are by kind permission of Tony Chetham, with my thanks, but he also sends a more recent picture of the Swimming Club: only the ruins of the pier remain.

School Holidays in England:

At the beginning of the Spring term of 1956 my brother Richard joined me at Glengorse, and in the Autumn term of 1958 I moved to Bradfield College, a public school in Berkshire. My parents felt they had to be in England for these moves, with the result that we did not spend the summer holidays of those two years in Mombasa.

At the end of 1955 my mother travelled to England with Richard by sea, on the Matiana, and my father flew home in time to join us for Christmas, which we spent with my aunt Noel, my mother's sister's family in London - picture above of my cousins Isabella and Michael with Richard and I. My father then flew back to Mombasa but my mother stayed in England until the end of the summer holiday, most of which....

....we spent at a farm near Launceston. Richard and I were devastated at not being in Mombasa for the eight-week holiday. We saw this as our compensation for the miserable months we spent in England. The best we could do was to wear our bush jackets, which my mother must have brought with her.

Once Richard came to Glengorse the various relatives who had shared looking after me during the Christmas and Easter holidays when my parents weren't in England couldn't be expected to look after two of us, so my mother found a lady who had a large house near Fareham in Hampshire who made a living out of looking after children such as us. My mother spent the Easter holiday of 1956 there with us, I suppose to check the place out, and that is where we spent all subsequent Christmas and Easter holidays.

Mrs Groome was kind, and the house, Tanners, was set in miles of open country. We helped with jobs around the property, which included walking the cocker spaniels which she bred - picture shows us with four generations of pedigree spaniels. However, my main memories of holidays at Tanners were that we were bored.

In 1958 my mother felt she needed to be in England again to kit me out for the move to Bradfield. She took a cottage near Appledore in Kent, and we spent the summer holiday there. Richard and I made friends locally and learned to fish for rudd, roach and perch along the Royal Military Canal. As a holiday it was okay but it just wasn't Mombasa.

The Hoey House 1957:

After spending the summer holidays of 1956 in England we were desperate to return to Mombasa in 1957 - but we had moved, off Mombasa island to the Nyali Estate along the coast to the north. My father had been promoted but the African Mercantile manager's house in Cliff Avenue needed extensive repairs so we had to make do with a rented house - but what a house!

It had been built by a 'white hunter', Cecil Hoey (more about him here). It was on a large plot by the sea, built in a slight curve with all the rooms facing onto a veranda, from which....

....the view looked across a lawn with scattered palm trees beyond which lay a white-sand beach and the sea; and beyond the beach lay a lagoon protected, two miles out, by a coral reef. For two small boys, this was paradise. The calm beauty of the place even seemed to affect my father, who was never normally willing to mow a lawn, let alone try to repair the mower.

All Richard and I wanted to do was to spend our time on the beach. No-one else bothered us on it. At high tide the waves could be fierce but we swam in them, or sat in our rubber inner tubes and bounced across them, and low tide exposed miles of rock pools filled with sea creatures. We collected shells. We walked along the high tide line picking up exotic flotsam from across the ocean. We made boats out of coconut husks and crewed them with hermit crabs. It was as much as our mother could do to persuade us to come indoors to eat and sleep.

We certainly didn't want to spend time in town, and seeing friends seemed much less important than getting out onto the beach. We did some of the usual things, like visit Tsavo East game park, but we didn't go to the Chini Club or Swimming Club as much - we didn't need to. Even Tsavo wasn't as wonderful as usual: a herd of buffalo came visiting the Hoey House, and green monkeys were often in the trees.

We gathered for sundowners on the veranda and watched the yellow weaver birds come to the bird bath. After supper we retired to bedrooms which opened on to the veranda, and slept with the doors open so we could hear the sea: there was a night watchman, who had been Hoey's gun bearer. He was armed with a wicked-looking, curved sword but he slept peacefully on a couch at the end of the veranda.

It was a wonderful holiday, which made the idea of returning to England even more horrible. I remember Richard and I sitting with our parents on the curved section of veranda which can be seen in the picture behind my father begging them not to send us back. Our pleas and tears made no difference. When it came to it we packed our suitcases, climbed meekly into the car and left this beautiful house.

Bradfield 1958:

So in the autumn of 1958, at the age of 13, I started at Bradfield. After Glengorse, it seemed huge, but from the moment I arrived I knew I would like the place. That said, life there for the first years was tough. Bullying was rife, some of it violent. The prefects wielded the cane. First years were assigned to a senior boy as his 'fag', to clean his shoes, lay the fire in his study, and do just about anything else he told us to. The common room in which we existed was bare and cold, the dormitories freezing, but the food was much better than at Glengorse, and in our own time we were free to roam in a way we'd never been allowed to there - we even brought our bikes and rode around the countryside.

The picture shows the 'House' to which I was assigned, 'D' House, consisting of some fifty boys aged from 13 to 18. It shared with 'G' House a large building on top of a hill about half-a-mile from the main school buildings. Our housemaster was Andrew Gimson whom I always found very fair.

We participated in some sort of physical activity on six afternoons of the week. Some of the sports were compulsory. This included cross-country running, which led up to the annual steeplechase in which, as well as fighting our way across muddy fields, we ended up climbing a weir of the River Pang which flowed through the school grounds. A large range of other sports was available, including squash, fives, tennis, shooting - at which I always did well - and archery.

The school was a soccer school and I worked my way from the house teams to the school teams, ending up in the second eleven. In the summer cricket and athletics were compulsory but I spent as much time as possible....

....at the school swimming pool. The contrast to Mombasa was stark: the pool was filled by the River Pang flowing in at one end and out at the other, so the water was permanently cold. Despite this, I made the school swimming team.

The school pushed its more able pupils hard. At an early stage someone decided that I should specialise in the sciences, so at age 15 I took five 'O' levels - English Grammar, English Literature, Maths, Latin and French - and then started three 'A' levels, Maths, Physics and Chemistry, taking them at age 17. As a consequence, I ended up with no qualification in subjects which would later interest me, and which I would teach - particularly History and Geography.

The Third Cliff Avenue House:

In the summer of 1959 Richard and I returned to Mombasa. We were disappointed that it wasn't to the Hoey House at Nyali - it seemed that nothing could possibly beat it - but the African Mercantile manager's house....

....was no disappointment. It was towards the end of Cliff Avenue, and overlooked the Mombasa seafront, the golf course, the channel along which the ships approached Kilindini, and a projection of the reef called the Andromache Reef, onto which the great seas of the Indian Ocean broke in a welter of foam.

Because there wasn't a beach on which to spend our day we had to find other amusement, and we found it in rediscovering our friends - the Chethams, Sollys, Ashworths, Champions, Milnes.... We played tennis at the Sports Club. We all had bikes so we roamed the town, spent time bartering for Kamba carvings along Salim and Kilindini Roads, and for kikois in the African markets, and explored the forgotten parts of the island. Our parents helped by organising trips to the Swimming Club and to the beaches to the north and south of Mombasa.

We also spent a great deal of time at the house. Its veranda looked out at the view but behind it was the sitting room in which my father had the first HMV stereo gramophone in East Africa - the African Mercantile was agents for HMV - so we spent hours playing records. We listened to 'pop', Elvis, Connie Francis, Buddy Holly, but we also enjoyed my father's collection of classical music, particularly Rimsky Korsakov's 'Scheherazade', Dvorjak's 'New World', and Holst's 'The Planets'. We sat on the veranda and the servants brought us Coca Colas, which my mother bought by the crate, roasted cashews, raw peanuts, and raisins.

The ships passed so close we could wave to people we recognised on deck. When one of my father's ships came in - this is a Harrison Line ship - and if the captain was a particular friend, we would hang coloured towels from the upstairs veranda as a signal to him; and, in due course, he would come to lunch and, more often than not, we would go aboard ship.

We returned to this lovely house for the 1960 and 1961 summer holidays.

The Aeroplanes:

The first 'plane on which I travelled alone to school in England, in 1954, was a Hermes, a four-engined propellor-driven aircraft in BOAC livery. I 'celebrated' my birthday in Mombasa on Saturday 2nd January so....

Second House in Cliff Avenue:

We didn't last long in the old bungalow in Cliff Avenue, moving a few yards up and over the road in early 1951 to this large, semi-detached house with its deep, cool verandas. In hot weather, Richard and I moved to sleep on the upstairs veranda where we lay in bed watching a gekko catch moths attracted to the wall light, and listening to the squeak of the bats hunting in the darkness.

There were snakes in the garden but a mongoose sometimes came to stay in the concrete water meter box visible on the right of the house - my mother encouraged it by leaving out the occasional chicken's egg.

As with the bungalow, the house was rented by my father's company, the African Mercantile. They must have taken the whole house as the married couple in the other half, the Oxley-Boyles, were colleagues.

The car my father drove, a Morris Oxford, was also the firm's. Most cars in those days were black, a very unsuitable colour in such a hot, sunny climate, but the Morris was dark green.

This picture, taken on the downstairs veranda, must have been very early on in our time in the house as Susie, Richard's dog, is little more than a puppy, while....

....this one is some time later as Richard is in primary school school uniform. While Richard is rather out-of-focus, the tennis court in the big, detached house next door is clearly visible. It was owned by the National Bank of India and had been divided into two flats. The Bains lived in one of the flats, and Hamish Bain became a good friend. Amongst other things, the tennis court made a great racetrack for our bikes.

We were also friends with the two children in the other flat, and the four of us formed a gang whose fortress was on the corrugated iron roof of the servant's toilet at the back of the house - which must have thrilled the staff.

I can't remember the girl's name but the boy, left, was called David. He always struck us as one of the kindest people we had ever met. This picture was taken at the Swimming Club in 1954.

Maths Test:

The old Arab chest keeps revealing its treasures. Mixed up in a pile of letters which date to the middle 1960s was this scrap of paper, a maths test which, at a guess, I took when I was about five while at Mombasa European Primary School.

I seem to have started the test well on the simple addition and subtraction of single digits but things started to go wrong with the first answer which involved tens as well as units, where I transposed the digits, making 14 into 41.

Multiplication obviously floored me. I love the 2 x 6 = 6, but it indicates that I had no concept of what multiplication was.

The teacher's comment is so revealing. "He can do + & - of tens and units, but was so worried today he didn't have time to do them." So I worried then, have continued to worry ever since, and have passed this talent on to some of my children.

Visiting Ships:

The African Mercantile's ships' agency side looked after the interests of a number of different lines. The 'Joint Service' included the Clan, Hall and Harrison Lines, while others included the Bank Line, the Scandinavian East Africa Line, and the French national line, Messageries Maritime. I always thought the best-looking ships were the Clan Line ships - picture shows the Clan Shaw.

When we first moved to Mombasa, my father was responsible for AMCo's ships' agency. His job was to look after all a ship's needs - so he went on board immediately a ship came in to see the captain and ask his requirements - but his main job was to oversee the unloading of the ship as quickly as possible and then to fill her 'down to her marks' - that is, so she was down to the Plimsoll line, as fully loaded as she could legally be.

My father's favourite line was the Harrison Line, in which his father had risen to be captain. Richard and I were often asked aboard ship, at least in part because my parents were extremely hospitable to all the captains, many of whom they came to know very well. The visit shown in this picture was particularly special. We are seen here on the SS Defender, our grandfather's old ship.

When we left the ship my father would often be given a bottle of something special which he had to hide as we went through customs. Another small 'thank you' came from some of the Clan Line captains who would give him a box of fresh kippers: my father did like kippers, if not quite as much as a Yarmouth bloater!

Some Harrison Line ships had heavy-lifting derricks and we would go down to Kilindini to watch them offload something unusual - like the huge Garrett locomotives that pulled the trains on East African Railways. Picture shows one of these ships, the Adventurer, from one of the paintings which Harrisons used in their annual calendar. The locos were so heavy that, as they were hoisted out over the wharf, the whole ship listed.

We would also go down to the docks to watch animals being loaded, destined for zoos in Britain. The conditions in which some of the animals were transported....

....would not be acceptable today. The crew had to care for their special cargo and this resulted in some interesting incidents, like when a hippo was being given a bath and escaped, rampaging round the ship. I also have vivid memories of a crate of ostriches being lifted onto a ship when the end of the crate opened and the three birds fell to the ground, killing them all.

Home Leave 1952/53:

My father's contract with the African Mercantile entitled him to three months 'home' leave every three years, and my parents decided that we should 'enjoy' the experience of a winter leave at the end of 1952. We sailed southbound on the Durban Castle, with my mother and Richard getting off at Beira and proceeding by rail to....

....Southern Rhodesia, to Bulawayo where my mother's sister, Christian Vigne, lived with her two daughters, whom my mother had never seen, while my father and I continued on the ship. At Durban I was impressed by the huge shark that swam alongside the ship while it was docked, and by the Zulus pulling rickshaws. My mother and Richard rejoined us at Cape Town, after which we called at St Helena, Ascension and the Canaries before arriving in England.

My parents took part of a flat in Fulham, in Hurlingham Court, overlooking the Thames close to Putney Bridge. The leave was extended into 1953 when a problem was identified on one of my father's lungs which required treatment by a London specialist. When the spring term started, Richard and I walked across Putney Bridge to attend a small private school as day boys.

While we were there my parents took me down to visit a school in Sussex. At the time I didn't understand the significance of this. Soon after, we returned to East Africa by air, using a service run by Hunting-Clan. The flight was by Viking, a 27-seat 'plane which was not particularly good for long-distance flights - it took three days to Nairobi via Malta, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, Juba and Entebbe.

Mombasa European Primary School:

My mother, in her "Life', records my joining the Mombasa European Primary School in 1950 as follows: "Jonathan started school as soon as we got to Mombasa, but the first day he came home in tears. Dad had told Miss Foat, the headmistress, that Jonathan was six and he had been put in with six year olds, and he was only five. I went to the school with him the next day and sorted things out.

"Richard and I used to walk up around 12 noon every day to the school pulling red wooden fire engines on string, Richard with his and I pulling Jonathan’s." The school was only a short distance from the house, along Cliff Avenue, and, from what my mother wrote, the school, certainly for five-year olds, closed at midday.

This picture shows me in MEPS uniform which consisted of a tie in white, black and yellow. We also had a piece of coloured ribbon sewn along the top of our breast pocket to show which house we belonged to. If my memory serves me, the houses were named after early explorers - Livingstone, Speke*. I can't remember which one I belonged to but my ribbon was red. On our feet we wore takkies - plimsolls - and an important item was a stretchy belt which was done up with an S-shaped metal snake.

My mother wrote that, "Jonathan had a good grounding at the school...." but my recollection is that I kept my head down in class and did as little work as possible. My mother used to call me a "dreamer".

Nor did I shine at sports, which is probably why the only athletic photo of me is in the obstacle race, when I recall vividly that I could not, just could not get a bite from that bloody bun. I may not have been any good at sports but that did not prevent me from joining in the football game which was played during morning break, when it seemed that all the boys ran onto the school pitch and chased a single soccer ball across its hard, dry, dusty surface.

There are only five photos in the family albums which relate to my brother and my times at the school. I presume that either Richard or I are somewhere in this picture of the school choir: I have no memory of singing in the choir.

I do, however, have vivid memories of the vital role I played in this play which I think was based on the story of Hiawatha. My friend from next door, Hamish Bain, suitably bearded, is at left, in the role of the white man, while Carol Miller, right, was Hiawatha. At one point, in order to impress the natives, Hamish had to raise his flintlock and shoot a bird out of the air. I provided the 'bang' as I had a clever little cardboard bang-making machine which had come free with the Topper, the comic which came out from England each week - Richard had the Beano.

At the prizegiving ceremony at the end of 1953 I received a prize for making good progress in my lessons.

One other memory of the school is that, each morning, we all paraded in front of the long veranda that ran along the outside of the classrooms for the raising of the union jack. It was quite a privilege to do the raising, and one day towards the end of 1953 I was given the honour. At the time I didn't understand why but shortly afterwards I was told by my parents that I was leaving the school.

*Tony Chetham has kindly corrected me: there were three houses, instituted in 1953, Mackinnon (red), Wavell (green) and Livingstone (blue).

MEPS Reports:

Some but not all of my reports from the Mombasa European Primary are in the old Arab Chest. This is the last one, dated December 1953. I'm not sure what 'Vernacular' was, unless it was the use of the spoken, as opposed to written word.

In a yesterday's post in which I described my time at the Mombasa European Primary School, I quoted my mother's story about my being enrolled by my father, who gave my age wrong, resulting in my being placed in a higher class, much to my distress. All my MEPS reports have my name as 'Jonathon', so it seems likely that my age wasn't the only thing my father got wrong.

The second page of Mrs Dalgleish's report states that I had 'gained in confidence'. Again, a teacher has put her finger on one of my weaknesses, a lack of self-confidence. The report also records that I was awarded the Progress Prize - a photograph of me receiving the prize at the end of the term is also in yesterday's post.

The Chini Club:

The Chini Club pool was so-called because it was below the Mombasa Club, 'chini' meaning 'below' in KiSwahili - this picture courtesy Tony Chetham. Before the coming of the Florida Club and the pool at the Oceanic Hotel, it was the only place on the island of Mombasa to which we could easily cycle for a swim - swimming in the sea off the island wasn't a good idea as the waters were the home of some rather unfriendly sharks.

At centre right is the covered area where drinks were served, and the changing rooms are in the white building to the right

The pool was built out on a coral platform and looked up to the old Portuguese Fort Jesus, at that time a prison. A wall, topped with broken glass, ran along that side to prevent access from the beach.

We loved it there. It was very private, the water was warm, and the pool was often almost deserted. The only disadvantage was that we had to have an adult with us.

I have no idea why Richard and I are wearing masks here! As far as I can remember, although the pool was filled from directly the sea and was, therefore, salt water, sea life wasn't common in the pool, though its sides did become quite slimy.

There were occasional events there: this picture, probably 1959 or 1960, was taken during one of the Club's galas. The view behind me is across the entrance to the Old Port to the reef at English Point.

Departure 1954:

I don't know how my mother was able to take this picture but it says something about her determination that this should happen and, perhaps, about her rather stern Scottish upbringing. In her photograph album she wrote underneath it, 'Departure'.

The small boy dressed in school uniform who is waving as he walks out across the tarmac at Nairobi's old Eastleigh airport is me. It's early January, perhaps 8th, 1954, I have just turned nine and, unlike my school friends who are going to secondary school in Nairobi, I am flying 'home' to England, 'unaccompanied' as BOAC termed it, to go to prep school. I wouldn't see my parents, or my Mombasa home, again until late July.

What the picture doesn't show is the state I was in.

Why didn't I run away across the tarmac? What was it that kept me going? A sense of duty? The blindness of tears? Or the incomprehension that this could be happening to me?

This picture was taken in late September 1954, after I had returned to East Africa for my eight-week summer holiday. It was taken at the African Mercantile offices on the day I left Mombasa to go to Nairobi on my way back to England, this time for ten months. Knotted up in my hand is a damp handkerchief. We were about to leave in the Morris Oxford, KAA 694. My father wasn't accompanying us so this was the moment when I said goodbye to him. Look just to the left of his head and there's a hand waving: it's the African Mercantile's driver, who was taking us.

I remember playing the mouth organ almost the whole way. Somehow the music, terrible player that I was, seemed to help. The picture was taken at the bridge over the Tsavo river.

This was the next day. I'm dressed in my prep school uniform ready to leave - the only thing I'm not wearing is the school tie - so this must have been taken shortly before I boarded the 'plane at Nairobi. Richard is wearing his MEPS hat.

Once again I ask - why did I go along with this? I had already begged my parents, again and again, not to send me back, so why hadn't I already tried to run far, far away? By now I knew what I was going back to, and it was a miserable place compared to Mombasa, the school almost a prison, the rain, the bitter cold of England's winter, the loneliness

In the Christmas and Easter holidays I stayed with an aunt and uncle in London. They were kind, but their children had already left home and I felt I was an encumbrance. There wasn't much to do, and London always seemed wet, grey and smelly.

For the next seven years this was the pattern of my life.

First Passport:

Until I was nine I had travelled on my mother and father's passports so I had to have my own when I went to school in England. It was issued in Mombasa on 10th December 1953 ready for my departure in early January 1954.

It used to be a very smart old-style, cardboard covered British passport but the gold of the royal coat-of-arms has been worn off the front and the black material of the cover is sticky.

As with so many things, it lived for years in the old Arab chest. Packaged with it are two subsequent passports along with other documents one had to have, such as a little yellow World Health Organisation booklet which contained records of yellow fever, smallpox, typhus, cholera and other vaccinations.

It was a Kenya passport so was issued by the governor on behalf of the Queen. In those days a stamp was affixed as a receipt for the payment made for the passport, a mere £1 - and what a beautiful King George VI stamp it is. The bit in blue at bottom right is important: I was born in Tanganyika, a UN Trust Territory, so had automatic right to pass full UK citizenship to any of my children who, like Katy, were also born abroad. This would not have been the case had I been born in Kenya, a colony.

When issued, the passport was valid for five years and was duly renewed, so it finally expired in December 1963. Even though it was a Kenya passport and my parents lived there, in order to return to the country I had to have....

....a valid re-entry pass. These were stamped into the back of the passport, and each lasted for two years.

The body of the passport contains the immigration stamps each time I entered Kenya. British immigration didn't stamp it, nor did Kenya normally stamp it each time I left, but on the occasion that our 'plane broke down in Rome and we were delayed for 24 hours while parts were flown out from England, the Italian authorities recorded both my entry and departure.

Glengorse - 1:

I attended Glengorse School from January 1954 until July 1958. Glengorse was a typical prep school, a boarding school with about eighty pupils aged between seven and thirteen. It occupied Telham Court (above), a large country house situated in rolling countryside near Battle in Sussex, built on the hill where William the Conqueror's army camped the night before the Battle of Hastings. The school was a business, owned by the headmaster, Robert Stainton, and his father-in-law.

The pupils were terrified of the headmaster. He was powerfully built with piercing blue eyes beneath bushy eyebrows, and he wielded the cane on any of the small boys who misbehaved. He was a keen sportsman - he had captained the Sussex cricket team - and had flown in Mosquitos in the war. This is a poor picture of him - I recall being very afraid when I asked if I could take a photo - but look at the postures of the pupils.

We had a strict regime, which included being sent to one of the several toilets each morning, and then having to report if our bowels had moved: if they hadn't, an intimidating matron dosed us on syrup of figs - ugh! We slept in large dormitories which were bitterly cold in winter, the food was bland and left us permanently hungry, and the regime required us to participate in sport every day except Sunday - and that was worse because we would go on a group 'walk', either into the country or, if it was wet, in a crocodile along the country roads.

Glengorse's extensive grounds included football, rugby and cricket pitches, and it had a gymnasium in which, along with gymnastics, the main event was the annual boxing competition. Everyone had to take part unless one obtained a note from matron - impossible - and we spent weeks training for it. In the autumn term we played soccer, in the spring term rugby, and in the summer cricket. Every week in summer we were taken to the White Rock swimming pool in Hastings.

In our last year, aged 13, we took the Common Entrance exam. The resulting grade dictated whether we obtained a place at the public school our parents had chosen for us. The school was, therefore, under considerable pressure to ensure that as many of its pupils as possible managed to get in to their first choice school.

Glengorse - 2:

I cannot describe how utterly miserable, how lost and abandoned I felt, when I first arrived at Glengorse. It was January, bitterly cold and torture for someone accustomed to Mombasa's climate. To cry publicly was to be reviled, so I cried myself to sleep at night, in a bed with a lumpy mattress where the only coverings were a sheet, blanket and thin quilt. The younger pupils were bullied. The regime was regimental. The lessons were in very small classes taught by men most of whom had been through the war - Maths was taken by a hideously disfigured and very bitter man who had 'brewed up' in a tank in the North African desert. Some of the staff were kind, fun even; some were cheerless, and one, a Mr Urch, was a bully.

One incident encapsulates my sense of abandonment. Every Sunday morning, after breakfast and before the school walked down in a 'crocodile' to Battle parish church for morning service, we sat in silence in our common room to write home. Our letters were corrected by the master on duty. If they weren't good enough, he would tear them up, but he couldn't tear up mine as I used an aerogramme. The very first time I wrote home I realised I didn't know my home address. The master stood over me. "Well, Haylett, what's the name of the road?" "Cliff Avenue, Sir." "Okay. Now what number is your house?" Number? We didn't have a number. We had a board outside which said 'Haylett'. The letter did reach home but it brought a cable to the school from my father. Our address was PO Box 110, Mombasa. I didn't know it.

Yet we survived. Small children learn to control their feelings, to bottle up emotion, to adapt to their environment, to keep their heads down and make the best of those things they can enjoy. Friendship was one of them. This group is pictured in front of the chapel, where we had a service twice a day; on Sundays we had three, including the walk down to the parish church.

Because my parents were abroad, I often had nowhere to go when pupils went home for half terms. Sometimes I would stay at the school and was allowed to spend my days wandering in the woodlands that surrounded the school. Roger Soole (left) took me to his home near Welwyn Garden City, a large farm where he, his parents and sister were warm and welcoming.

Occasionally, my Aunt Noel would drive down from London on a Sunday and do what other pupils' parents did on a fairly regular basis: take me out for a hearty lunch. These parents unwittingly gave their son some food to take back to school - a fruit cake, a jar of jam. This was taken away, and had to be shared around the table with the other pupils.

We were fairly obsessive about food. Some puddings were rather good, including a chocolate semolina pudding. One boy who was serving at table was asked what was for pudding, to which he replied 'Thames Mud', which is what we called this pudding. The headmaster overheard him and took him straight to his office and caned him. At mid-morning break we had a cup of tea and half a slice of white bread, with a sweet. After lunch on Sundays, as a treat, we had two Cadbury's 'Quality Street' chocolates.

Sport helped. I wasn't particularly good but good enough to play in the first eleven/fifteen in soccer, rugby and cricket, and good enough in all to earn the accolade of 'getting my colours'. In cricket, which I didn't really enjoy, I kept wicket and batted towards the end of the order. This is a picture of the cricket first eleven, probably in 1958. I stand, as in so many pictures, slightly away from the group.

In my last year, 1958, I was made a prefect. In Art, a subject taken by Mr Stainton, the headmaster, I won the annual prize - and upset him by choosing scuba diver Hans Hass' 'Under the Red Sea' as my prize rather than a book about great artists. I left the school without any regrets.

Glengorse Reports:

The contents of the old Arab chest are witness to the mementos my mother most wished to keep, like, for some reason, all my school reports. Many of the things she seemed to treasure I have thrown away to make space for those of the next generation's things which I consider important - mainly photographs.

However, I did keep my Glengorse reports, at least in part so that I could try to remind myself of how I survived there, but the sheer blandness of the comments destroys any such hope. The report above was for the end of that first, traumatic term in spring 1954. I love the Geography report, "Fair only. Rather bewildered at present but improving rapidly," and the Games one, written by Mr Stainton, the Head, "A very promising footballer, he is calm and aggressive." Well, I would be, after learning my skills on the rock-hard surface at Mombasa Primary School where hoards of boys of every size pursued a ball which frequently disappeared into a thick cloud of dust.

This is my last report from the school, for the summer term 1958. It reminds me that I learned Latin, well enough to translate chunks of 'Caesar's Gallic Wars', which I did not enjoy, and French, where I had the serious handicap that, when I wracked my brain for a French word, it often came out in Swahili.

"A thoroughly confident swimmer," remarks Mr Stainton in 'Gymnasium', perhaps forgetting that I came from Mombasa. He goes on to write, against the 'Games' heading, "He was very keen and only (though it is the hardest thing to say) needs to get some confidence as the result of effort and experience," which is roughly what Mrs Dalgleish said in her report when I left MEPS some four years previously - see earlier post here.

Summers in Mombasa 1954 & 1955:

I spent the summer holidays of 1954 and 1955 at the house in Cliff Avenue. I saw some friends from my days at MEPS but going to school in England had separated me from them. My mother took us to the Chini Club and across to the Swimming Club, and she organised picnics at the beaches to the north and south of Mombasa, but I remember being very content with my own company.

My parents had friends called the Dingles who ran a chicken farm to the south of Mombasa. Once a week, Mr Dingle came in to town in a dark green Morris Minor van to delivered eggs. Each holiday we drove out to visit them. Their farm was on the coast, with a fine white-sand beach, and they lived in palm-thatched 'bandas' in what seemed very primitive conditions - but I loved it there, and one holiday I stayed with them. The picture shows my father with Richard and I sitting on the side of an open, concrete water tank. There seemed to be thousands of chickens in the runs beyond the house, and I helped to feed them and collect the eggs.

The Dingles gave us a chicken. She had a large tuft on her head and was christened Clario. According to my mother, "She shared Tinker's food and laid an egg every day except Sunday. The boys would fight as to who should have the egg; to solve the problem Clario invited another hen to join her in egg laying so that we had two."

The Ansteys were also good friends of my parents. They had a house at Tudor, where this picture was taken. Mr Anstey was manager of the East African Breweries. Richard and I are in the Anstey's garden in typical daily wear: tee shirts, shorts, 'tackies' - plimsolls - and we always wore a small sheath knife - Richard's is visible in the picture.

The Swimming Club:

In her 'Life' my mother wrote, "After Sunday School the boys and I would return to the house and get our tricycles and my bike and swimming suits and go down to the Chini Club for a swim before returning to the house for lunch. Or we would go right down to the landing stage and get a rowing boat to take us across to the Swimming Club where we would eat our lunch which we took with us, and spend the afternoon swimming and playing in the sand, usually with the Solly boys and Margaret who sometimes took us over in her car. Dad would come later, having been at the Sports Club watching cricket, and take us home in the car."

This picture looks back across the Old Port to the Old Town, with a number of dhows at anchor. The Swimming Club's raft is at centre, with a line of tyres which acted as a safety line if someone was swept away by the current.

We were rowed across in a small boat - seen at left - which came in to....

....the end of the Swimming Club pier - one of the boats can be seen near the pier. The club building was set up back from the beach and always seemed rather dark and damp. Occasionally, if it rained heavily, we were forced to take shelter there, which we didn't enjoy. It had one attraction to some members of the community: it had the only fruit machine.

Sometimes there were events at the Club. This group photo was taken on the steps of the club house.

The top three pictures are by kind permission of Tony Chetham, with my thanks, but he also sends a more recent picture of the Swimming Club: only the ruins of the pier remain.

School Holidays in England:

At the beginning of the Spring term of 1956 my brother Richard joined me at Glengorse, and in the Autumn term of 1958 I moved to Bradfield College, a public school in Berkshire. My parents felt they had to be in England for these moves, with the result that we did not spend the summer holidays of those two years in Mombasa.

At the end of 1955 my mother travelled to England with Richard by sea, on the Matiana, and my father flew home in time to join us for Christmas, which we spent with my aunt Noel, my mother's sister's family in London - picture above of my cousins Isabella and Michael with Richard and I. My father then flew back to Mombasa but my mother stayed in England until the end of the summer holiday, most of which....

....we spent at a farm near Launceston. Richard and I were devastated at not being in Mombasa for the eight-week holiday. We saw this as our compensation for the miserable months we spent in England. The best we could do was to wear our bush jackets, which my mother must have brought with her.

Once Richard came to Glengorse the various relatives who had shared looking after me during the Christmas and Easter holidays when my parents weren't in England couldn't be expected to look after two of us, so my mother found a lady who had a large house near Fareham in Hampshire who made a living out of looking after children such as us. My mother spent the Easter holiday of 1956 there with us, I suppose to check the place out, and that is where we spent all subsequent Christmas and Easter holidays.

Mrs Groome was kind, and the house, Tanners, was set in miles of open country. We helped with jobs around the property, which included walking the cocker spaniels which she bred - picture shows us with four generations of pedigree spaniels. However, my main memories of holidays at Tanners were that we were bored.

In 1958 my mother felt she needed to be in England again to kit me out for the move to Bradfield. She took a cottage near Appledore in Kent, and we spent the summer holiday there. Richard and I made friends locally and learned to fish for rudd, roach and perch along the Royal Military Canal. As a holiday it was okay but it just wasn't Mombasa.

The Hoey House 1957:

After spending the summer holidays of 1956 in England we were desperate to return to Mombasa in 1957 - but we had moved, off Mombasa island to the Nyali Estate along the coast to the north. My father had been promoted but the African Mercantile manager's house in Cliff Avenue needed extensive repairs so we had to make do with a rented house - but what a house!

It had been built by a 'white hunter', Cecil Hoey (more about him here). It was on a large plot by the sea, built in a slight curve with all the rooms facing onto a veranda, from which....

....the view looked across a lawn with scattered palm trees beyond which lay a white-sand beach and the sea; and beyond the beach lay a lagoon protected, two miles out, by a coral reef. For two small boys, this was paradise. The calm beauty of the place even seemed to affect my father, who was never normally willing to mow a lawn, let alone try to repair the mower.

All Richard and I wanted to do was to spend our time on the beach. No-one else bothered us on it. At high tide the waves could be fierce but we swam in them, or sat in our rubber inner tubes and bounced across them, and low tide exposed miles of rock pools filled with sea creatures. We collected shells. We walked along the high tide line picking up exotic flotsam from across the ocean. We made boats out of coconut husks and crewed them with hermit crabs. It was as much as our mother could do to persuade us to come indoors to eat and sleep.

We certainly didn't want to spend time in town, and seeing friends seemed much less important than getting out onto the beach. We did some of the usual things, like visit Tsavo East game park, but we didn't go to the Chini Club or Swimming Club as much - we didn't need to. Even Tsavo wasn't as wonderful as usual: a herd of buffalo came visiting the Hoey House, and green monkeys were often in the trees.

We gathered for sundowners on the veranda and watched the yellow weaver birds come to the bird bath. After supper we retired to bedrooms which opened on to the veranda, and slept with the doors open so we could hear the sea: there was a night watchman, who had been Hoey's gun bearer. He was armed with a wicked-looking, curved sword but he slept peacefully on a couch at the end of the veranda.

It was a wonderful holiday, which made the idea of returning to England even more horrible. I remember Richard and I sitting with our parents on the curved section of veranda which can be seen in the picture behind my father begging them not to send us back. Our pleas and tears made no difference. When it came to it we packed our suitcases, climbed meekly into the car and left this beautiful house.

Bradfield 1958:

Amongst the many things I have found which my mother kept in the old Arab chest is the slip of paper my parents received announcing the results of my Common Entrance examination - the test taken by all those seeking a place at a public school. Although both my maternal grandfather and my mother's brother had gone to Harrow, I had been put down to go to Bradfield College in Berkshire where cousins of my mother's, the Humphries, had gone. The results surprise me in their variability - 98% for geometry yet 47% for algebra - and in how well I did in subjects I hated, such as Latin.

The picture shows the 'House' to which I was assigned, 'D' House, consisting of some fifty boys aged from 13 to 18. It shared with 'G' House a large building on top of a hill about half-a-mile from the main school buildings. Our housemaster was Andrew Gimson whom I always found very fair.

We participated in some sort of physical activity on six afternoons of the week. Some of the sports were compulsory. This included cross-country running, which led up to the annual steeplechase in which, as well as fighting our way across muddy fields, we ended up climbing a weir of the River Pang which flowed through the school grounds. A large range of other sports was available, including squash, fives, tennis, shooting - at which I always did well - and archery.

The school was a soccer school and I worked my way from the house teams to the school teams, ending up in the second eleven. In the summer cricket and athletics were compulsory but I spent as much time as possible....

....at the school swimming pool. The contrast to Mombasa was stark: the pool was filled by the River Pang flowing in at one end and out at the other, so the water was permanently cold. Despite this, I made the school swimming team.

The school pushed its more able pupils hard. At an early stage someone decided that I should specialise in the sciences, so at age 15 I took five 'O' levels - English Grammar, English Literature, Maths, Latin and French - and then started three 'A' levels, Maths, Physics and Chemistry, taking them at age 17. As a consequence, I ended up with no qualification in subjects which would later interest me, and which I would teach - particularly History and Geography.

The Third Cliff Avenue House:

In the summer of 1959 Richard and I returned to Mombasa. We were disappointed that it wasn't to the Hoey House at Nyali - it seemed that nothing could possibly beat it - but the African Mercantile manager's house....

....was no disappointment. It was towards the end of Cliff Avenue, and overlooked the Mombasa seafront, the golf course, the channel along which the ships approached Kilindini, and a projection of the reef called the Andromache Reef, onto which the great seas of the Indian Ocean broke in a welter of foam.

Because there wasn't a beach on which to spend our day we had to find other amusement, and we found it in rediscovering our friends - the Chethams, Sollys, Ashworths, Champions, Milnes.... We played tennis at the Sports Club. We all had bikes so we roamed the town, spent time bartering for Kamba carvings along Salim and Kilindini Roads, and for kikois in the African markets, and explored the forgotten parts of the island. Our parents helped by organising trips to the Swimming Club and to the beaches to the north and south of Mombasa.

We also spent a great deal of time at the house. Its veranda looked out at the view but behind it was the sitting room in which my father had the first HMV stereo gramophone in East Africa - the African Mercantile was agents for HMV - so we spent hours playing records. We listened to 'pop', Elvis, Connie Francis, Buddy Holly, but we also enjoyed my father's collection of classical music, particularly Rimsky Korsakov's 'Scheherazade', Dvorjak's 'New World', and Holst's 'The Planets'. We sat on the veranda and the servants brought us Coca Colas, which my mother bought by the crate, roasted cashews, raw peanuts, and raisins.

The ships passed so close we could wave to people we recognised on deck. When one of my father's ships came in - this is a Harrison Line ship - and if the captain was a particular friend, we would hang coloured towels from the upstairs veranda as a signal to him; and, in due course, he would come to lunch and, more often than not, we would go aboard ship.

We returned to this lovely house for the 1960 and 1961 summer holidays.

The Aeroplanes:

The first 'plane on which I travelled alone to school in England, in 1954, was a Hermes, a four-engined propellor-driven aircraft in BOAC livery. I 'celebrated' my birthday in Mombasa on Saturday 2nd January so....

....from the timetable I might have caught flight BA162 on either Tuesday 5th or Thursday 7th, leaving Nairobi Eastleigh at 09.00 and arriving, via Entebbe, Khartoum, Cairo and Rome, at Heathrow the following day at 10.10. At each stop the passengers disembarked during the scheduled refuelling and drinks were served in the airport lounge. This should have taken an hour although, over the years of these journeys, some of these stopovers were often far longer.

The Handley Page Hermes was a development of the military Hastings, an aircraft rushed into service shortly after the Second World War to fulfil the need for transports during the Berlin Airlift. As a passenger 'plane the Hermes was noisy and unreliable, so it often arrived late, but it was far quicker than the Solent flying boat it replaced, which had taken three days to reach the East African coast from Southampton.

The Hermes did not last long in service, giving way to the no less noisy but slightly more reliable Canadair Argonaut. My England-bound flight on an Argonaut in September 1955 shed a large part of the port outer engine over the Mediterranean. The captain was quick to walk down the aisle and reassure the passengers, and we learned from one of the air hostesses that we really didn't need to worry: the captain had flown Lancasters over Berlin during the war and had lost much bigger lumps off his machine.

However, the damage meant we had to stay the night in a very posh Rome hotel. The children on board, of which there were many in the same circumstance as me, took advantage of the situation by running amok in the hotel - I have happy memories of repeated slides down the ornate bannister into the foyer - so the staff hired a coach in which they could confine us while they drove us round and round the city until we were exhausted.

In its turn the Argonaut was replaced on BOAC's routes by....

....the 'whispering giant', the Bristol Britannia, the first 'plane on which it was possible to balance a pencil on its end. The Britannia, with its turboprop engines, was a huge step forward, quieter, reliable and comfortable.

I subsequently flew in a Constellation, an American aircraft, and, with some excitement, in my first jet, a De Havilland Comet 4. The last 'plane in which Richard and I flew as unaccompanied schoolboys was a Boeing 707.

The UK international flights came in to Nairobi and we connected to Mombasa either by car, a rough journey down what was still a mainly dirt road, by overnight train, which was very comfortable, or by air. The workhorse of the local air routes was East African Airways' Douglas DC-3 Dakota. The above picture was taken by my mother. There is no caption but I suspect that it was the one time when Richard and I flew to Nairobi with my father, when we hit the worst thermal I have ever experienced as we came in to land at Embakasi airport.

The Handley Page Hermes was a development of the military Hastings, an aircraft rushed into service shortly after the Second World War to fulfil the need for transports during the Berlin Airlift. As a passenger 'plane the Hermes was noisy and unreliable, so it often arrived late, but it was far quicker than the Solent flying boat it replaced, which had taken three days to reach the East African coast from Southampton.

The Hermes did not last long in service, giving way to the no less noisy but slightly more reliable Canadair Argonaut. My England-bound flight on an Argonaut in September 1955 shed a large part of the port outer engine over the Mediterranean. The captain was quick to walk down the aisle and reassure the passengers, and we learned from one of the air hostesses that we really didn't need to worry: the captain had flown Lancasters over Berlin during the war and had lost much bigger lumps off his machine.

However, the damage meant we had to stay the night in a very posh Rome hotel. The children on board, of which there were many in the same circumstance as me, took advantage of the situation by running amok in the hotel - I have happy memories of repeated slides down the ornate bannister into the foyer - so the staff hired a coach in which they could confine us while they drove us round and round the city until we were exhausted.

In its turn the Argonaut was replaced on BOAC's routes by....

....the 'whispering giant', the Bristol Britannia, the first 'plane on which it was possible to balance a pencil on its end. The Britannia, with its turboprop engines, was a huge step forward, quieter, reliable and comfortable.

I subsequently flew in a Constellation, an American aircraft, and, with some excitement, in my first jet, a De Havilland Comet 4. The last 'plane in which Richard and I flew as unaccompanied schoolboys was a Boeing 707.

The UK international flights came in to Nairobi and we connected to Mombasa either by car, a rough journey down what was still a mainly dirt road, by overnight train, which was very comfortable, or by air. The workhorse of the local air routes was East African Airways' Douglas DC-3 Dakota. The above picture was taken by my mother. There is no caption but I suspect that it was the one time when Richard and I flew to Nairobi with my father, when we hit the worst thermal I have ever experienced as we came in to land at Embakasi airport.

Many thanks to Tony Chetham for pictures of the Argonaut Hermes.

Letters Home:

In all the years I was at school in England I wrote to my parents weekly. I never spoke to them on the telephone - it was impossibly expensive - and I am only aware of one occasion when my parents sent a telegram, or 'cable' as they called it, and that was not to me but to the Glengorse headmaster when I sent my first letter home to the wrong address.

At Glengorse all the boys were sat down in silence each Sunday morning in the house room to write to our parents. They were checked by the master on duty and corrected or, if necessary, rewritten. This is one of the few surviving letters from that time, written in October 1955 when I was ten. My parents were on their way to England with Richard on leave, but would leave him at Glengorse for the spring term.

We were told never to write anything that might worry our parents. Had we done so, the letter would have been torn up. So the contents are utterly bland.

Although there was no requirement to do so, I continued to write home once a week from Bradfield. This air letter is fairly typical. It continues for half a page on the other side. While there was much more in these letters they continued to be determinedly positive, despite the fact that they weren't checked by anyone.

The letter is dated 19th July 1959 at the end of my first year at the school, the last letter before I flew back to Mombasa for the summer holidays. During that year I had experienced and witnessed some horrific bullying. It was institutional, all-pervasive, sometimes sadistic. Some boys suffered particularly badly - fortunately, I wasn't one - and all one could do was to give these unfortumates what support was possible. None of this ever appeared in a letter.

The habit of writing to my parents continued through my university days and well into my twenties, when Gill and I were abroad. Almost all these letters are in the old Arab chest.

'The Boys':

'The Boys' weren't boys at all, they were grown men, the servants who worked for us around the house. They cleaned the place, they did the laundry, they polished shoes, brass and silver-work, they tended the garden, they cooked and served the meals, they woke us in the morning with the tea tray, they babysat Richard and I when our parents went out in the evening.

When we first came to Mombasa we employed two, a cook and Ouma, the houseboy, who later became our cook and stayed with us until we left. By the time we moved to the third house in Cliff Avenue, our last house in Mombasa, we were cared for by four - from left to right, Mlalo, Ouma, Saidi - who always wore a red fez - and Kitetu. This picture was taken in 1959.

Ouma was a Jaluo from the Lakes. He lived on the premises and was joined at times by his wife and several children who normally stayed at their little farm, or shamba. The oldest was Barasa, and we came to know him well. Ouma was a bit of a dandy but a very intelligent man who, given different circumstances, would have gone far in life. He had a fine sense of humour and was incredibly good to Richard and I, for at times we teased him.

His dishes were legendary. He had been taught to cook by my mother but he picked up recipes from all over the place. While he could produce a classic English meal like roast lamb and mint sauce, he was at his best with fish. I will never forget his fish with cheese sauce, nor the way he would cycle down to the fish market on my mother's black Raleigh bicycle and come back with a live lobster or two in the front basket, to plunge them into boiling water.

Saidi (left) was a coast Swahili, a reserved man who waited at table, served drinks on the veranda or in the sitting room, cleaned the principle rooms, and brought tea to the upstairs veranda just before six and gently roused us so we could drink it and watch the sun rise over the sea.

Kitetu (right) was the dhobi boy who did our washing, and ironed it with a large iron filled with glowing charcoal. A quiet, unassuming man, Kitetu was also responsible for cleaning the brass ornaments, including the big Arab tray, using half a lemon and dirt. Saidi and Kitetu polished the downstairs floor which was red-painted concrete. They each had two coconut husks which they stood on and slid around the floor, singing as they worked.

Saidi and Kitetu served at meals, and served drinks on the veranda. At such times they wore a khanzu, and red cummerbund and fez.

Mlalo was the garden boy. He may have been the most lowly of the four but I spent hours with him, squatting next to him as he manicured the pathetic grass of the lawn or as he tended his eternally-burning bonfire. I was attracted by his simplicity, by the slow process of conversation with him, and by his sudden laughter. I teased him: if I found a chameleon I would bring it to him, knowing full well that he was terrified of them. It was Mlalo who made our catapults, a new one for each holiday, which we used to kill small birds.

Saidi and Ouma both spoke good English but all conversation with the boys was in KiSwahili.

My mother was responsible for the staff and it is a credit to her management that we had a minimal turnover. We trusted them implicitly, even through the times of Mau Mau when many worried about their servants. As far as I was concerned, they always seemed to be part of the family.

Summer 1961:

The summer of 1961 was the last school holiday we spent in Mombasa. My father's company, The African Mercantile, had been taken over by a big Australian firm called Dalgety who, while they wished to retain my father, were adamant that he had to move to a senior position in Nairobi. None of us liked Nairobi, it would have meant my father losing touch with his ships, and the uncertainties of Kenya's independence was nearing, so he opted to retire.

Dalgety's were very good to him, giving him a pension - which the African Mercantile had never offered. Picture shows the African Mercantile offices in Kilindini Road which were built while my father was manager.

By 1961 our circle of friends had widened further. We went out with the 'gang' every day. I was sixteen, girls were of considerable interest though I was too timid to do anything about it. We went to parties, various parents organised trips along the coast to some of the superb beaches which are now major tourist destinations - picture shows Richard and I at the Two Fishes on one of those outings - we went to the drive-in cinema and to....

....the Tsavo game parks where masses of elephants and buffalo still roamed - though, from the grainy photos which our Kodak 127 took, one might not believe it.

As the date of our return to England and to school approached our friends began to disappear back to school. In the last few days everyone had gone except for Christine, seen on the right here with my old friend Tony Chetham before he went back to school. Christine - sadly, I cannot remember her surname - was also shortly to return to school in England and we had a great deal in common, so we could help bury the misery of approaching departure in each other's company. I recall sitting on the front veranda of our house on the last morning feeling very low when Christine arrived and helped me through the last few hours before....

....Richard and I had to say a last goodbye to the 'boys' and to....

....the house which we had so come to love. This view from the upstairs balcony is from a painting given to my parents a few months later on their departure by Commander John Hall who, with his wife Kitty, were great friends of theirs.

This photo was taken by my mother as we left the house. I'm not sure why Gabriel, the company driver, is in the picture but we went to the station to catch the sleeper train to Nairobi. I remember the train crossing Makupa causeway as it left Mombasa island, with the sun setting behind the escarpment in the west, and swearing that I would never forget that moment - which, obviously I haven't.

I found this site via google idly searching for The Chini Club. Fantastic to read, thank you for putting your experiences online.

ReplyDeleteI found this site similarly, searching for something now forgotten! I loved reading it, as I spent the first 10 years of my life in Tanganyika, albeit being born in 1951. It brought the atmosphere right back. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteJill GIbbard

So pleased to hear from you, Jill. So many memories.... Jon

ReplyDeleteWhile in the Marine Corps, our ship made a stop in Mombasa, 1980. Went on to Diego Garcia and returned back to the Mediterranean. Fond memories. Loved you story.

ReplyDeleteI had lived in that house from 79 to 95. Great memories. Please share more pictures.

ReplyDeletePost more fotos

ReplyDeleteI came across this blog and was delighted to read particularly Mombasa, where I was born and lived until I was almost 12. We also lived in a bungalow on Cliff Avenue and latterly in Nyali. This blog brought back many happy memories of my life growing up in Kenya, thank you.

ReplyDeleteI'm so pleased you enjoyed the blog. When were you in Mombasa? Jon

DeleteThank you for your excellent story of your upbringing in Mombasa.I was born June 1941 in Nairobi and experienced the same wonderful childhood as you. From the age of 13 I also flew to UK for boarding school education and yes i was on the same flight as you I think we stopped at Entebbe then Cairo or Benghazi then Rome. After Take off I dozed and was woken by an Air Hostess to be told an engine had stopped and the pilot did not fancy flying over the high Alps so we were landing back at Rome. We were taken to a great Hotel in Rome - fancy 3 teenagers let alone in Italy any boyhood dream coming true! We snaffled a small bottle of red Wine and I experienced my first ever alcohol.What wonderful memories ! We always travelled down by overnight train to Mombasa every Christmas for !0 days staying at the Nyali Beach Hotel where I ate my first green chilli and scored my first ever Bull at darts. We were so, so lucky. All the very best to you. Thanks again. Robin

ReplyDeleteHello Robin, how good to meet again through the wonders of the internet! Yes, they were wonderful days in East Africa but we paid the price of ten months in England for each summer holiday in paradise.

DeleteIt has given me great pleasure to write my memories of those days but it is so good to hear that others have enjoyed reading them. Incidents like that night at the Rome hotel still raise a smile: I was not a wicked child but I remember not giving a damn about the trouble I might get into - it was a release from the misery of flying back to England.

With very best wishes. Jon

I was searching for memories from childhood: Kikambala, Vipingo, Tiwi, Salim Road, Cliff Avenue - and stumbled across your blog.

ReplyDeleteMy parents lived in Mombasa from 1947 to 1960, first at Cliff Avenue, then Nyali.

I was born there in 1953, and also went to MEPS! My brother Maarten was born in '42 and spent those years there too, boarding later at Prince of Wales in Nairobi.

My father was in charge of East Africa for the Holland Africa Line, (H/O in Kilindini Road), so must have known your father, being in the same sort of business. He also started a coastal feeder service.

I don't know if I am just overly nostalgic, but we had a unique childhood, and I am very excited to come across your blog which validates my experience too.

The pics of the Nyali pontoon bridge, Likoni ferry, etc. etc.

I also have an (unopened) Arab kist full of memories, so 'll have to tackle that now.

So much to discuss, I wonder if we could connect privately?

Paul Heering

Very interesting read. I found it whilst trying to research a family member that moved from England to Kenya in 1950... Thanks for the insights.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment. So pleased you found something of interest in the blog. Jon

DeleteI thoroughly enjoyed your reminiscences. I grew up in Rhodesia during the 50s and 60s so your account of Colonial African life invoked a lot of fond memories.

ReplyDeleteSo pleased you enjoyed the blog. Jon

Delete